At CUNY’S Lehman College, in the Bedford Park neighborhood in the Bronx, spring is on the cusp of full bloom: birdsong chimes from the budding trees; students congregate in the courtyards. Many yards below them, however, is a storied maze of tunnels connecting most of the campus’s buildings, and which today I have come to explore. I am guided in my spelunking by the deputy director of public safety, Greg Nigri, in his thirty-second year in the position and wearing an official CUNY jacket studded with pins and badges; and Janel Martinez, Lehman’s social media specialist, who is in her sixth month in the job and is delighted to be learning more about the college’s underbelly. Here they are, standing at the entrance to the longest, straightest stretch of tunnel beneath the campus. Like proper Virgils, they have brought an enormous key ring (Greg) and a notebook (Janel) to chart our journey.

Few people are aware that during World War II, the college, which was then Hunter College, and all-female, became a training ground for eighty thousand Navy WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteeer Emergency Service). The network of tunnels was used by the military to transport and store secret materials, and perhaps even weapons, to keep them out of sight of enemy air spies. The groups of hale and smiling volunteer women provided the perfect cover for the covert facilities beneath their oxford-clad feet. The campus also served as the very first, albeit temporary, home of the United Nations, whose security council convened here from March through August of 1946.

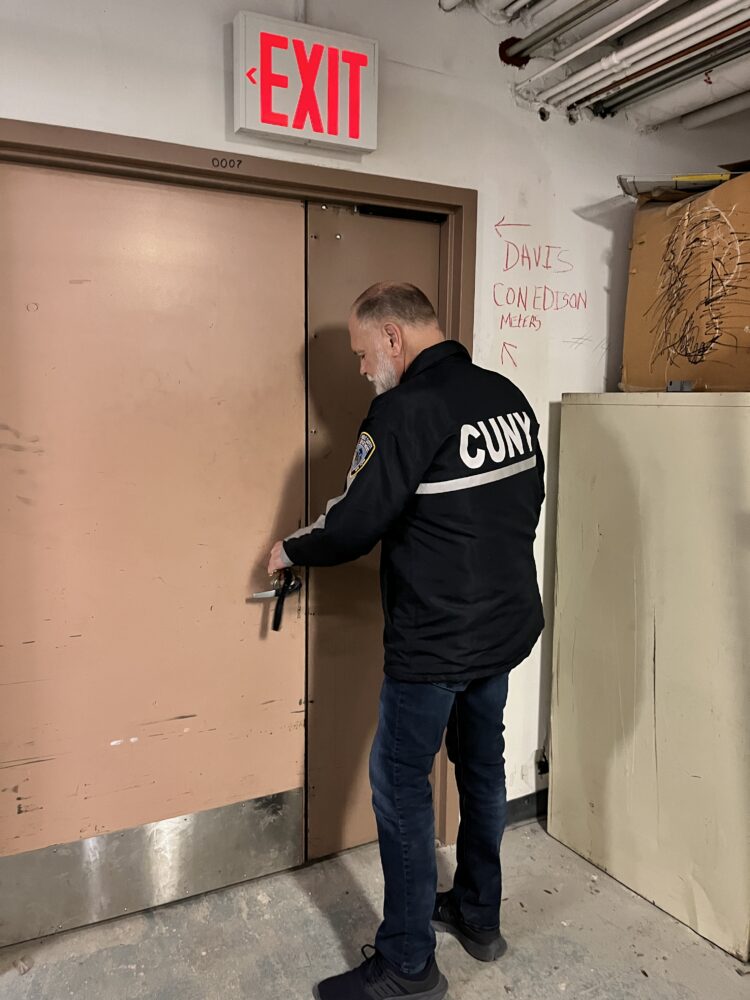

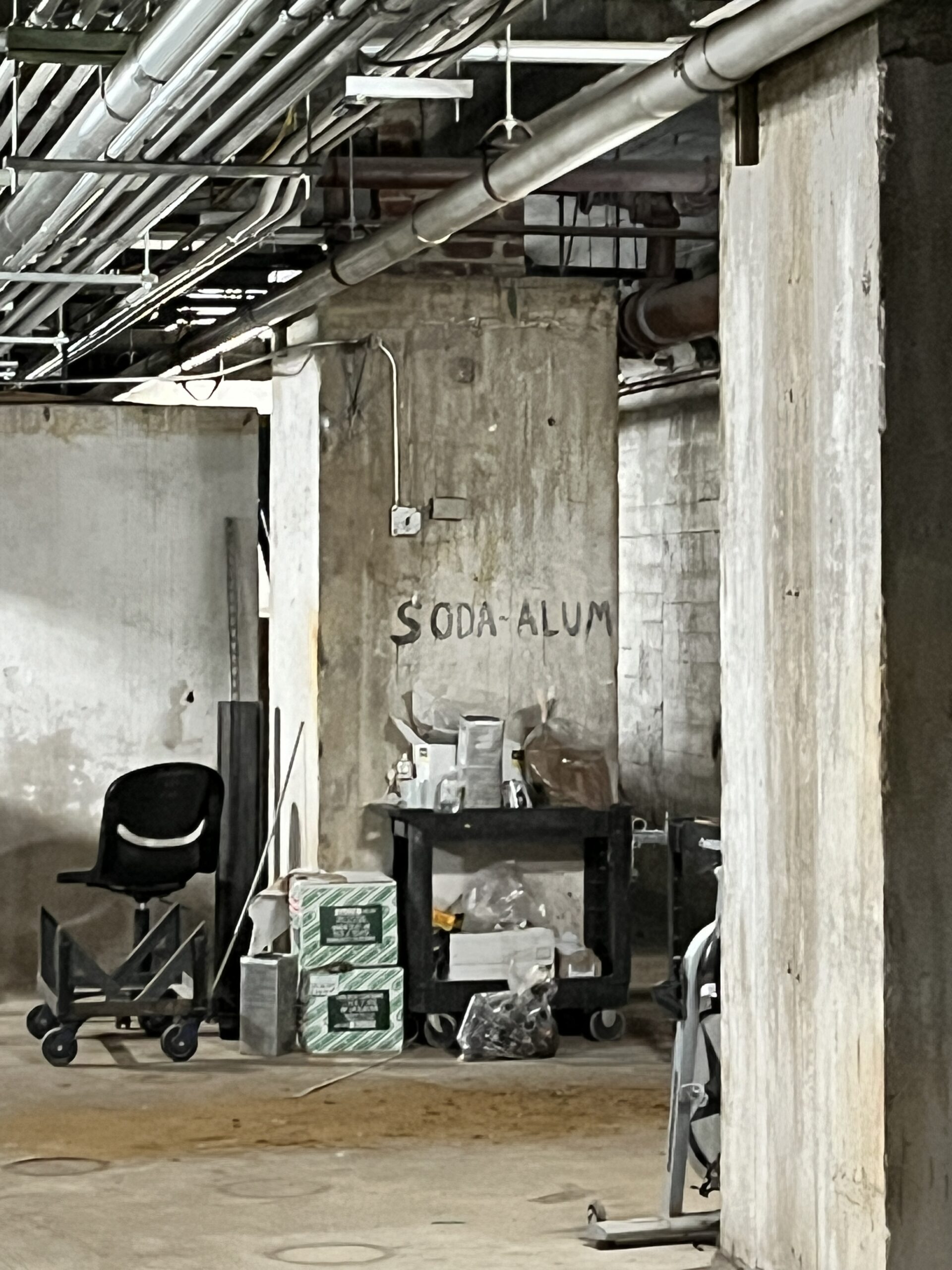

Jingling his keys, Greg lets us in through the first of many unmarked doors. We don’t know this yet, but the cryptic handwritten directions on the wall, as well as the phalanx of overhead pipes, the battered file cabinet, and the cardboard box (which appears to be marked with a scribbled-out ear?) are harbingers of the sights that await us.

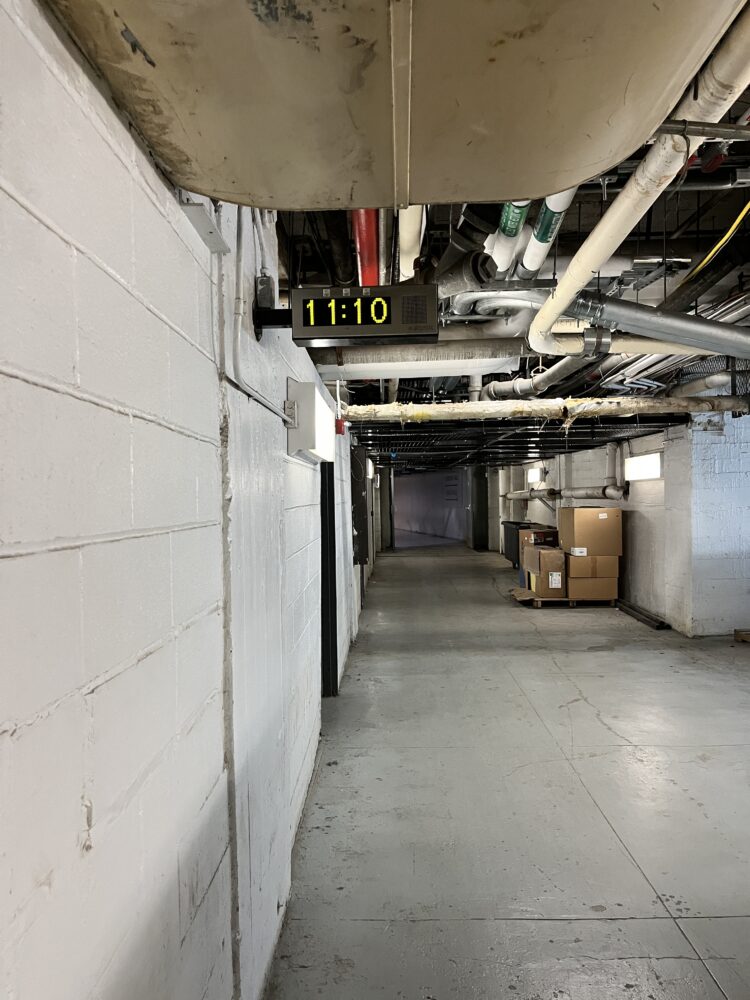

The tunnels have that signature midcentury smell of shiny, hot painted metal and the zing of electricity. Cell service fizzles out, but the space is dry and warm, lit by slabs of humming fluorescent lights mounted to the walls. Our only connection to the outside world is now a series of Big Brother–esque digital clocks that protrude from the walls at regular intervals. Greg explains that the displays are also equipped to transmit messages in the event of an emergency, though, fortunately, he’s never had to use them for anything more dire than announcing fire drills.

For the most part, the tunnels are a study in white, alarm red, and military gray-green, with the occasional spurt of yellow insulation.

At one point, however, Greg leads us through a “No Admittance B&G Only” door and into a dark room that is like a secret box of crayons in the bowels of the campus. The machinery, ladders, handcarts, and spools of wire are a delight to the eyes, as are the room’s purposeful grunts and groans and hisses from the tangle of pipes leading up to classrooms and offices, where students sit, oblivious to the color factory puffing away to keep them comfortable, clean, and safe. We happen upon two workers in hard hats consulting clipboards in a corner, who look alarmed by our sudden appearance.

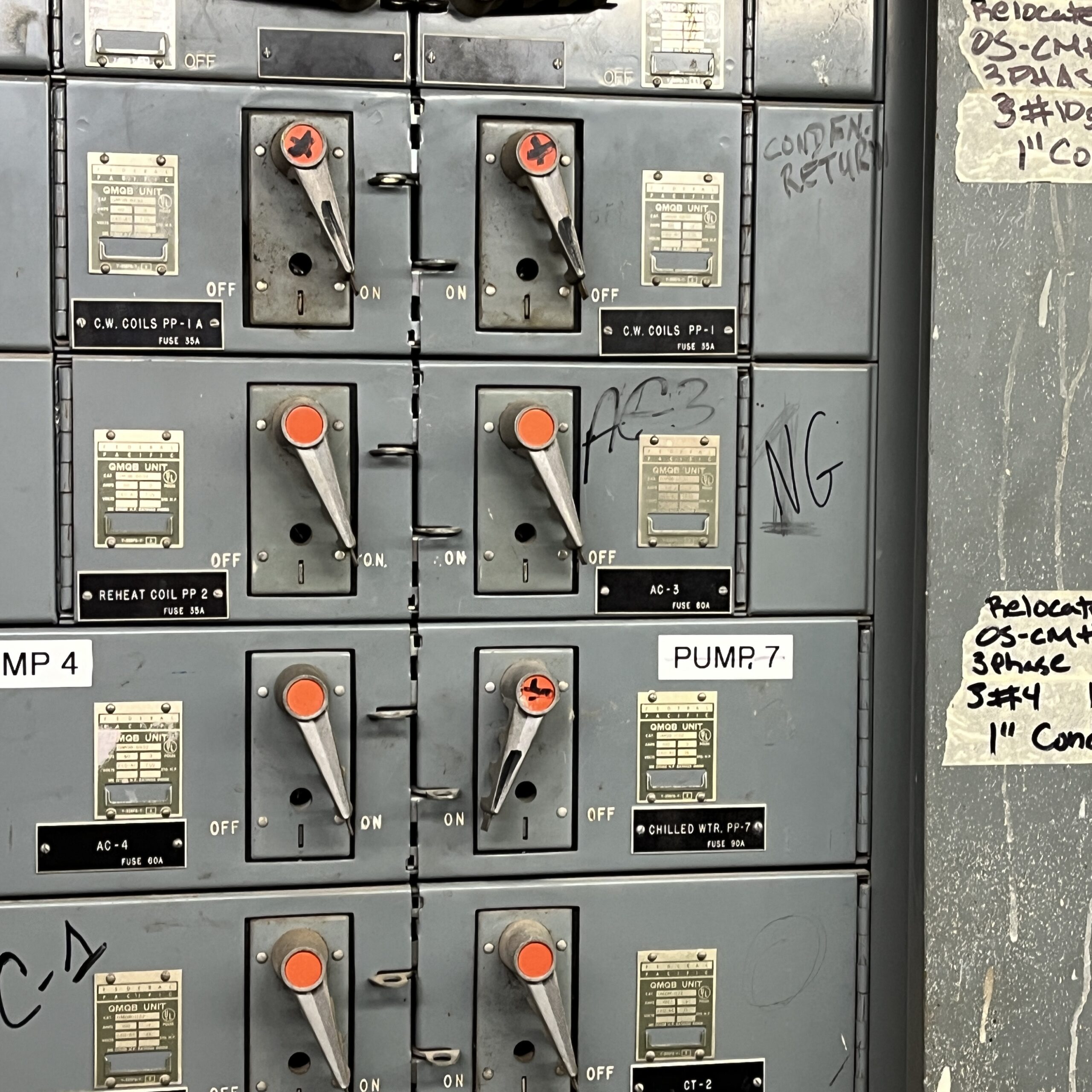

One wall in this room is covered in switches and valves and gauges, labeled in code: condensers, pumps, alarm systems, conduits, feeders, fuses. Beyond that, impossibly, through a hole in the Sheetrock and under a duct, we reach the end of one tunnel.

Two trapdoors in the wall suggest former passageways for supplies, though this is unconfirmed by Greg.

We spot occasional relics of leisure pursuits: a fallen basketball hoop, an abandoned shopping cart, a rusty, decades-old tin of Pathmark “Electric Perk” coffee with, appropriately, safety gear close at hand.

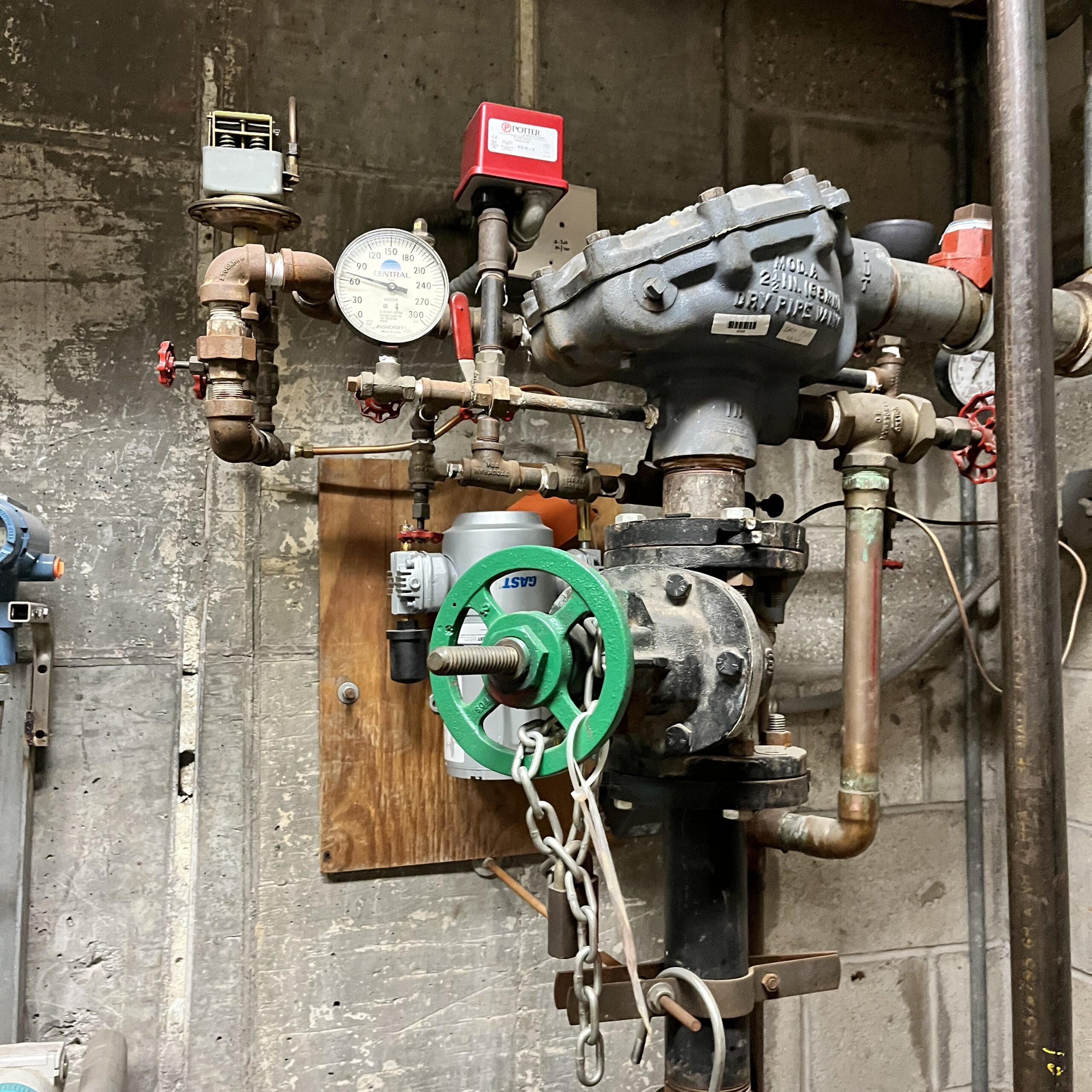

Gauges and wheels pop up in unexpected places, giving me the impression I could steer the impressive ship of this college campus from any passageway.

We see palimpsests of painted signs from the 1900s overlaid with modern signage. Abandoned office chairs are a frequent occurrence.

Through another unmarked door is an impossibly narrow and low-ceilinged tunnel hemmed in by pipes, with bulbs in cages, in which we hear whirring and clicking and the swushing sound of water. Here is Greg ducking into that tunnel. One pipe is marked “Chilled water return.”

When we emerge into a hallway and through a door at the other end, we find ourselves facing the school’s Olympic-size pool, the vast chlorinated water shimmering beneath the skylights, searing our nostrils. We breathe in as our eyes adjust to the aboveground world. We haven’t seen many people on our journey, though parts of the tunnels are accessible to students and staff. A few workers have trundled past pushing large plastic tubs whose wheels bump over the concrete floor, echoing off the walls. One man rounded a corner with a giant metal cart bearing a single plastic-wrapped bowl of salad. Janel is now eager to show me the college’s two historic bells and an ambient sound installation, as a counterpoint to the growls of the college’s underworld. One of the bells, from the U.S.S. Constitution, was given to the college to commemorate its role in the war efforts. Janel gives it a hearty ring, which resounds in the open air, tolling this chapter in the college’s history.

Inside the Information Technology Center is a motion-activated sound sculpture called Sonic Pass Blue by Christopher Janney, installed in 1999. It occupies a tunnel joining two parts of the building, but in this case light streams through blue-and-green-tinted windows from adjacent courtyards. Sensors near the floor pick up the motion of passing feet, and speakers emit the subtle calls of birds, gongs, and pluckings. Janel explains that Sonic Pass Blue is meant to provide a soothing and meditative transitional space, a quite moment between two places. In the middle of the tunnel I spot a green arrow sign pointing to the right—this one printed and framed rather than scrawled on the wall—but this time I decide to keep walking toward the light.

With gratitude to the late William B. Helmreich and his wife, Helaine, who alerted me to the existence of the Lehman sub-basement in their book The Bronx Nobody Knows: An Urban Walking Guide and on the Untapped New York podcast. And of course to Janel Martinez and Greg Nigri at Lehman.

Sense & the City is a monthly blog exploring the hidden corners of New York City. Each month’s post is devoted to one of the five senses. Receive daily sensory impressions via Instagram @senseandthecity.

Sense & the City is a monthly blog exploring the hidden corners of New York City. Each month’s post is devoted to one of the five senses. Receive daily sensory impressions via Instagram @senseandthecity.